Since 2020, Americans have experienced historical shifts in labor, employment and demographics that are reshaping all aspects of work. This includes where work is done (remote, hybrid, in office), who does it and why. Before I dive into the why, I would like to dispel a preconceived notion that has permeated both mainstream media and online echo chambers.

Myth: The Great Resignation Was Led By Gen Z and Millennials

Forbes, in 2021 explained in “Why Millennials and Gen Z are Leading The Great Resignation Trend” that the rise of hybrid teams and flexible work policies has made it easier for employees to change jobs frequently, contributing to the “Great Resignation” and leading to higher turnover rates for companies. Research by CareerBuilder highlights generational differences in job tenure:

*Baby Boomers stay in positions for an average of 8 years and 3 months due to their historical context and values.

*Gen-Xers stay for about 5.2 years influenced by their desire for autonomy and stability.

*Millennials average 2 years and 9 months, driven by their quest for work-life balance and meaningful work.

*Gen Z enters the workforce with an average job tenure of 2 years and 3 months, prioritizes meaningful employment and cultural impact.

This implies companies need to adopt more personalized approaches to attract and retain talent across different generations

Reality: Demographics and economics were key factors.

Harvard Business Review in 2022 found five factors that contributed to employer shortfalls: retirement, relocation, reconsideration, reluctance, and reshuffling (the five 5rs) are the main culprits and due to the sheer volume of baby boomers retiring, shortfalls were going to happen anyway.

This chart outlines this fact:

Average Monthly Quit Data

Data on total employment from 2009 – 2019 reveal that Great Resignation is not a pandemic driven anomaly.

What is “Reshuffling”

Reshuffling revolves around employees leaving lower skilled, lower paying jobs for jobs with better wage and growth prospects. Bharat Ramamurti described the ongoing high turnover rates in low-wage sectors as the “Great Upgrade,” with industries like accommodation, food services, and retail experiencing the highest quit rates. This trend isn’t just about workers leaving their jobs; many are moving to new positions within the same or different sectors, driven by the lure of higher wages and better job opportunities. Companies, recognizing the need to retain and attract employees, are responding by increasing wages and enhancing benefits. For instance, McDonald’s raised its hourly wages and benefits, leading to a higher staff count by the end of 2021, while Walmart’s Live Better U program aims to cover college tuition and books to improve worker attraction and retention.

The blind spot I commonly witness from business journalists, opinion leaders and most rational ‘hard scientists’ is a coherent reason for why these things are happening? Specifically, I believe it is important to delve into four key items.

- Which factors influence career choices?

- Why are shortages prevalent in many industries?

- What role does an individualist or collectivist disposition have on career selection?

- How are we addressing these issues?

What Drives Employment/Job Selection

For the sake of simplicity, I will distill job selection (holding everything equal) from the employee side down to

- Pay

- Demands Of Work (Mental & Physical)

- Qualifications

- Availability (Location)

- Prestige

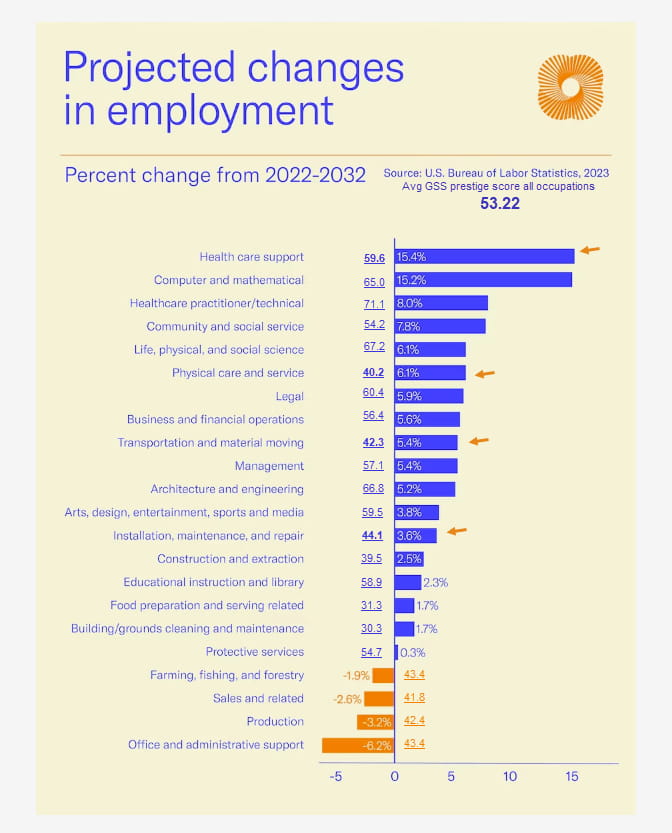

The last factor, prestige is rarely spoken about as it touches on the taboo subject of social hierarchy and class distinctions. However, it is abundantly clear that, with notable exceptions, like mathematicians, scientists, engineers, the lower the prestige score, the greater the shortage in absolute terms. The anomaly is with health care support, where there are shocks on the demand and supply side, which are demographically driven by early retirees leaving the labor forces, especially nurses AND more retirees using health care resources as Baby Boomers age. The chart below outlines occupations in demand and their respective prestige score.

The GSS, General Sociological Survey, collects information biannually and keeps a historical record of the concerns, experiences, attitudes, and practices of residents of the United States. It has been in operation since 1972 and works in conjunction with the University of Chicago and the National Opinion Research Center.

Does Prestige Matter?

Economists Corneo and Jeanne (2010) looked into how people’s beliefs and values might influence a country’s economic growth over time. They also considered whether a country’s level of development could change people’s beliefs and values, creating a two-way relationship that makes things more complicated. The study finds that in a growing economy, the happiness people get from spending money is important when they choose their careers, especially when looking at how much more respect some jobs have over others compared to how much more money they might offer. If people really care about the respect or prestige of a job (high elasticity), they might choose it even if it doesn’t pay much more than other jobs. This is because the status or respect they get from their job is more important to them than the extra money they could earn doing something else.

For students preparing to graduate from college or trainees entering the workforce, happiness or satisfaction is derived from two main sources: the money they can earn because of their hard work and education (this is called pecuniary returns from developing their skills or human capital) and the good feelings they get from being part of a certain group (nonpecuniary identity payoff). How much money they can make depends on their natural talents and how much effort they put in, after considering the costs of putting in that effort. The good feelings from being part of a group depend on how well a student fits with the group’s ideals based on their own characteristics and actions.

To be happiest, students try to find the best mix of hard work and which group they belong to. Choosing which group to belong to involves balancing the happiness they get from being part of that group against how well they naturally fit into the group based on its expected behaviors and characteristics. This concept was explored by economists Akerlof and Kranton in 2002.

The trade off between social prestige and economic prestige was quantified by economists Humlun, Kleinjans and Nielsen in their paper An Economic Analysis of Identity and Career Choice. The authors concluded that traditional economic theories struggle to explain why some people choose careers or education paths that don’t promise high financial returns, even though they require similar levels of investment. A model inspired by Akerlof and Kranton (2000) suggests that people make these decisions based not only on the financial rewards (pecuniary factors) but also on how these choices affect their identity and self-image (non pecuniary factors). This idea was tested using data from Danish students, which showed that career and social orientations significantly influence their educational choices, highlighting the importance of prestige in these decisions.

The study found gender differences in how identity factors influence educational choices. Women are more likely to choose their education level based on prestige factors, with career-oriented individuals gravitating towards fields like business, law, social sciences, engineering, and natural sciences. Socially oriented people, regardless of gender, prefer humanities, natural, or health sciences. These preferences suggest that educational choices align with the behaviors expected from career-oriented or socially oriented individuals, indicating that prestige plays a significant role in these decisions.

Humlun, Kleinjans and Nielsen’s findings suggest that educational policies and reforms should consider both financial incentives and prestige-related issues. This could involve information campaigns to help people make choices that align with their self-image or changes in educational content and extracurricular activities to attract the types of students educators want. This approach is particularly relevant for higher education in the U.S. and for broader educational policy in many European countries, where government policy influences student enrollment capacities.

In short, educators, employers, government policy makers, and professional trade organizations have an obligation to increase the prestige of occupations that have important tangible and intangible impacts. Celebrities, for example, score high on prestige and they connect us culturally, emotionally and in some cases spiritually. On the other hand, workers that keep the lights on, ensure safe transportation of goods, provide empathetic care or repair our air conditioners also provide value but it’s not reflected in their overall GSS scores.

So,

[1] Should we use celebrity to attract talent into much needed occupations?

[2] How do we collectively and authentically respect and pay homage to unsung occupations that serve us on a daily basis?

[3] How do we increase the occupational prestige of areas in high demand?

As both a father and a concerned citizen, I welcome any and all recommendations as this situation needs a collective, cohesive and holistic response.